McClaren F1

A hyperexotic, accompanied by glamour, glitz, technical wonder—and penguins too

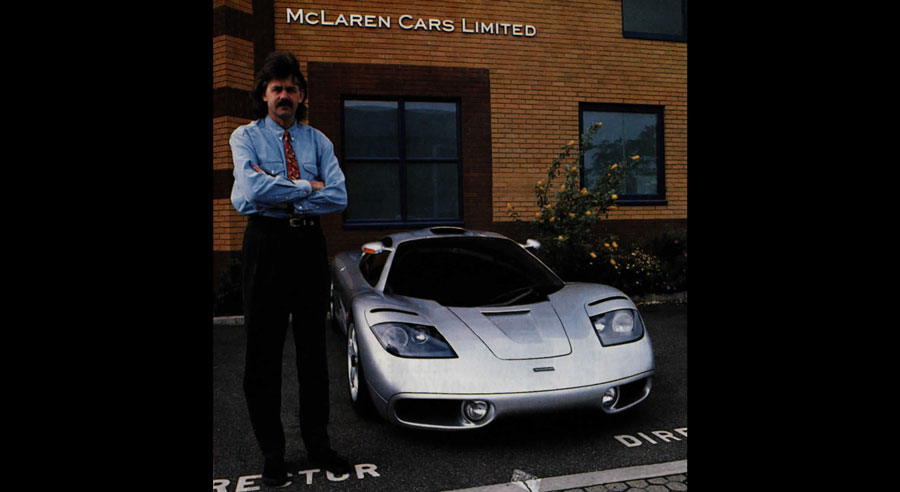

The Setting was glamorous indeed: ‘The Sporting Club of Mo-naco, Thursday evening before he Grand Prix. Elegantly dressed people. Marvelous music (of which more anon). At center stage, circled by benchmark cars bearing the McLaren name, was a mysterious shape draped in silver. Everyone knew it had to be the McLaren F1 hyperexotic. Then came the glitz: mellifluous tones from the master of ceremonies, swirly multicoloured lights, dry-ice mist. The silver cloth was pulled away—to reveal not McLaren’s new road car, but last year’s all-conquering MP4/6! A subtle joke, that. Then, rising out of the mist came another silver shape; this one, the object of everyone’s interest. The car, says technical director Gordon Murray, “represents the pinnacle of 20th century high-performance sports-car design.” A heady claim, indeed, were it from any company but McLaren.

Consider just a few of its features: a carbon-fiber monocoque defining a properly swoopy shape, 1+2 seating with central driving position, fan-assist-ed ground-effect aerodynamics, electronically controlled brake cooling, active aerodynamic center of pressure control, 6.1-litre BMW V-12 power; engine management and other electronics linked by modem to McLaren head-quarters. The list goes on.

But what’s most telling is the car’s philosophical positioning among the world’s exotic cars. The F1 is replete with technicalities, yet firmly grounded in McLaren basics; it’s innovative, yet conservative. For instance, its powertrain has no traction control of any sort, and its brakes are non-ABS, in fact, non-assist-ed. Instead, a Brake and Balance Foil is hinged into the rear deck. Under heavy braking, this airfoil angles automatical-ly for optimal grip and stability. And, in a latter-day adaptation of Murray’s 1978 Brabham BT46B fan car, two high-power electric fans remove the turbulent boundary layer from the un-derbody to enhance efficiency of the car’s downforce-generating diffuser. Let’s pay less heed to several of the car’s claimed “firsts,” especially when one can nitpick priorities.

As one example, a central driving position with a passenger seat set back on each flank isn’t new. It was an equally controversial feature of the Ferrari 365P executed by Pininfarina (R&T, November 1991). This time around, Murray says the layout has proved its practicality. How-ever, I must admit that no one was al-lowed to try it out in Monaco; admittedly, the Fl there was a mockup, a “clinic model,” not a fully engineered runner. It certainly looked inviting enough. What’s more, any of the three seating positions is said to accommodate a 95th-percentile adult, no doubt even the 6-ft. 5-in. Murray himself.

Unlike some other exotic cars that come to mind, there are no hardships here. Air conditioning, tailor-made leather luggage, a carbon-composite document case, a fitted titanium tool kit, and, from Kenwood, the world’s most compact 10-disc CD player. My music of choice? Simon Jeffes’ Penguin Cafe Orchestra: the same whimsically minimalist music that orchestrated the Monaco introduction—specially chosen by none other than Gordon Murray!

Certainly inviting, but you’ll have to wait your turn: 50 cars per year, the first in late 1993, at some $980,000 each; a maximum run of 300 cars by century’s end.